WWMAPS Project

Guidelines for Team Organization and Processing

Ver. 01 - 25/09/05

RP

|

WWMAPS Project Guidelines for Team Organization and Processing |

Ver. 01 - 25/09/05 RP |

1. How partners can collaborate

The WWMAPS project focuses on the concept maps as they represent a dynamic, and world wide recognized code to create and share knowledge models. In fact the concept maps structure requires few terms, short phrases and its structure is language independent [1], as can confirm anybody have translated them. Each language has a basic structure: subject-verb-complement, which form propositions or the “knowledge unit”. These propositions or “knowledge units” form the concept map. The concept maps are also the clearest and most useful way to show and support - at a metacognitive level- any change occurring when students add new knowledge to the previous one.

If the knowledge representations are very complex and comprehensive it is advisable to arrange them in a set of CMaps and resources, instead of crowding all in one single CMap. This set of CMaps is known as knowledge model and it is usually indexed to a single “Home Cmap”, to which the other CMaps are linked and where it is possible to have a sight of the whole organization.

CmapTools is unique to grant a public and free server network which allows the co-operation teams to arrange their knowledge models in the web, managing document files as they do in their home computer desktop.

The asynchronous activities related to creation of shared knowledge are the most frequent. These occur when those who co-operate (students and/or tutors) have access to the resources at different times. The resources are studied, viewed or edited, but if they are modified a good feedback with your partner is required, and their restoring at the original status must be granted if needed.

Just with one click, CmapTools also allow the synchronous collaboration. Nevertheless this is rare since it requires simultaneity in the kids’ working hours, which is hard to set among foreign countries and sometimes also within the same country.

Sessions of synchronous collaboration can be arranged among co-ordinators teachers. CmapTools supports each session of synchronous collaboration by a private chat. Staff of the wwmaps project is at disposal to grant any functional and useful supports, also beyond those you can get from the hyperlinks in this document.

2. Examples of distant co-operation procedures among partners

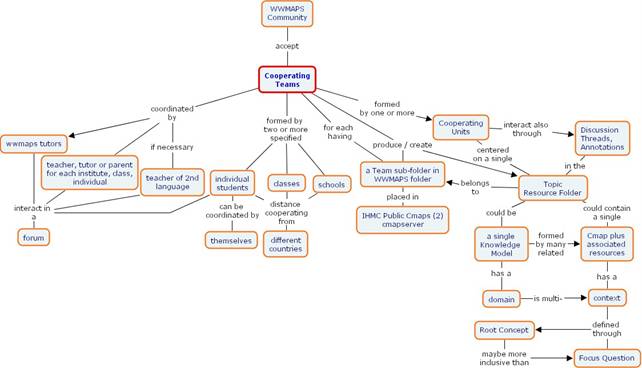

If you are a member of WWMAPS Community and if you match in one or more subjects with a partner, you can create your distance co-operation team. This team would include those teachers who have joined the project, the students or groups of students involved, any additional teacher (i.e. for foreign languages or technology devices) and a tutor from the WWMAPS Staff.

Every co-operating teams would be part of the WWMAPS Community and would chose the common forum, available at www.2wmaps.com/bbforum, for any communication but the ones relating to the maps contents (for which will be used Annotations and Discussion Threads, both supported by CMapTools).

The project aims at promoting both the co-operation and the interaction among students in the CmapTools environment, without wasting time in sideways discussions. The co-ordinators teachers would support the organization and use the WWMAPS Forum as well.

The main parameters for the different forms of co-operation are three: complexity, reciprocity and autonomy.

Complexity: it assesses the frequency, the diversification level of the various ways of communication, the kind of knowledge resources and representations required to grant a systematic nature to the knowledge building and interchange process.

Reciprocity: it refers to the interaction and interdependence indexes required to the co-operating students.

Autonomy: degree of independence of activities from the tutors’ and teachers’ co-ordination.

|

Examples of collaboration modalities |

Parameters (1 = minimum, 2 = medium, 3 = high) |

||

|

Complexity |

Reciprocità |

Autonomy |

|

|

1. Each partner develops a CMap on a common subject and checks his partner’s work. By sharing and comparing talks and notes, information is exchanged. |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

2. Both the partners work on the same CMap: they edit it in turn and they establish rules to inform each other about any additional content or alteration. Nevertheless there is no division of their tasks and of the knowledge domain. They must interact and discuss to reach an agreement too. |

2 |

3 |

2 |

|

3. Both the partners work on the same complex map, or on the same knowledge model, by proposing and agreeing the sub-contents to develop. Connections among sub-contents are also possible, even if they belong to different maps. |

3 |

3 |

2 |

There is no limit as for the division in class groups and the choice of their subjects and sub-subjects. Each class can be divided into several groups, formed by single students, “twinned” with distant partners. Each class can be partitioned in groups, or even single students, “twinned” with distant partners. All the students or the groups can work on the same subject in parallel, or else they can deal with several peculiar subjects. The co-operating unit is a sub-group formed by those who, within the co-operation team, participate in one single resource shared in the net (concept map or knowledge model). Each co-operating unit is represented by a single folder, which contains the cmap, additional related resources, or a family of related cmap and further resources (knowledge model). The folder of the co-operating unit can be a separate folder in the server used by wwmaps, if it coincides with the co-operation team. Otherwise the co-operating unit folder becomes part of a wider folder of the team, if various contents are developed in it and if students are co-ordinated in different ways.

Each new formed team must choose the most suitable organization and expect-evaluate any possible route change during the process. Instead the staff of the project is responsible for the supervision and updating of the MeToo map of all the teams. There is no limit as for the number of partners whom each class can interact with. Nevertheless each team must be a clearly defined group with specific co-operating units. For instance, if a school class in Costa Rica chooses 2 partners from 2 foreign countries, (Italy and Panama for instance) the class will participate in two different co-operation teams, each one formed by 2 or 3 countries.

3. How to

overcome the linguistic differences

As already stated, the concept maps maintain their structure regardless of the language used and translations of concept maps are much easier than those of plain texts. In fact any map uses a basic language, with easy words and no metaphors at all. Therefore concept mapping language becomes suitable to explain and share knowledge clearly among different cultures and languages.

If both the partners can’t share any common language, they must work on multilingual maps, where English or Spanish are the “joint links”(in figs 1-5 the Spanish language is the link between Quechua and Italian). Foreign languages teachers would provide assistance to pass from the spoken to the transition language and vice versus: kids can also do it with the help of a tutor when L2 is taught in their school.

There are on line translators as well (http://www.ecuaventura.com/diccionario/palabras.cgi, http://www.worldlingo.com/en/products_services/worldlingo_translator.html) to make the task easier.

|

1. Initial map |

2. Spanish translation |

|

3. Italian translation made in Italy |

4. Italian kids add further propositions |

|

Let’s imagine a collaboration between Ecuador and Italy for instance. Ecuadorian kids would start a map in quechua language and make a Spanish version to edit. Then the project committee would translate the Quechua – Spanish map into a Spanish-Italian one. Italian kids would edit the map in Italian and their teachers or someone else from the wwmaps committee, would translate the new words from Italian to Spanish and send the map back. There, the Ecuadorian teachers and kids would translate the map in quechua or in Spanish. The alternative interchange language could be English. |

5. Any additional proposition is translated in Spanish too, before sending the map back to Ecuador. |

If the CMap is a very simple one, a tri-lingual version can be developed as well (i.e. fig 6). Very complex and crowded CMaps would have just a monolingual version. One single document can contain two identical complex maps in two different languages. (i.e. fig. 7). In this case there are two advantages: a) knowledge soups can be used b) in a map slight differences can be added, in relation to the differences in the structure of the two languages.

|

Fig. 6 A basic CMap can be developed in 3 languages as well |

Fig. 7 Complex maps can be developed in parallel into two separate languages either on the same page (English on the left side and Spanish on the right in the given example), or on two different cmap files. |

Of course during the inter-exchange stage, new important propositions, resources and revisions are added. Any CMap develops according to the working process of the students with their teachers. This kind of maps would be called “living maps”.

According to the constructivist theory, any mistake occurring in one of the maps edited by the students is a welcome part of the knowledge process. In fact the quality and the essence of the interaction are much more important. The co-operating teams are responsible of the contents.

4. Themes of interest for the co-operation

The concept maps are created by assembling propositions and starting from the most comprehensive concept of a certain dominion (Ruth Concept). Nevertheless they are neither mere graphical presentations of knowledge (hypertext), nor the way to develop and create ideas and associations (mental maps) starting from this concept. In fact the concept map is the answer to a specific question (Focus Question), and while it “presents” a structured knowledge domain, it also tends to provide answers and explanations. The content of the focus question determines which concepts are inside or outside the “frame”. On the contrary, the map extension capability would be unlimited and arbitrary, and there would be the risk of a meaningless development. If the context is clearly specified the shared concept map is a valid tool to show how students can adjust new knowledge with the pre-existing one [2], [3].

On the whole it would be impossible to give suggestions about the possible subjects for the co-operative work on the maps. Everything being of common interest, could promote the collaboration between two or more partners.

On the other hand, given the extraordinary opportunity of developing a valid, co-operative distant learning experiences, it is advisable to find contents of cultural inter-exchange which wouldn’t be never developed in the single local curriculum, anyway. Let’s think to geographical, social, environmental themes, educational and political systems, free time, jobs etc, which always differ in the foreign countries and societies the partners belong to.

The main areas can be: (the following categories are arbitrary)

|

Field |

Area |

CMap Topics samples |

|

Anthropological |

Geographical-Historical |

Physical, social, political, economical Geography. Ages, History of populations and races. Geographic discoveries, Migrations, Reigns/Empires, Revolutions, Civilization. |

|

Social Science |

Human Rights; Ethics; Democratic Social Coexistence; social, political, work organization. Ethos and Values. |

|

|

Cultural Expressions |

Literature, graphic arts, crafts, music, cinema, sports… |

|

|

Religion |

Religious Orders, Believes and Rites, The Holy Scriptures, Religions Hist., Religions coexistence, Relationship between Faith and Science |

|

|

Events – Topics |

Natural Events; Social and Political Events; daily life |

|

|

Logical-mathematical scientific |

Environmental Education |

Resources; Air, Water, Ground Pollution, Bio diversity, Waste, recycling etc. |

|

Science Experimental Inquiring |

Projecting Experiments, reports of research and revision of inherent concepts |

|

|

Natural Science |

Disciplines (Physic, Chemistry, Biology, Astronomy etc.) |

|

|

Technology |

Technology Arts, Computer technology, work projecting and realization |

|

|

Mathematics |

Set Theory, Movement, Geometry, Logic, Arithmetic, Measures, Data elaboration, Problems, Algebra, Statistics… |

Learning of a second language

The Concept Maps promote the learning of a second language through:

translation from the map L2 into the text in L1 and vice versus, from the map in L1 into the text in L2

creation of the map in L1 starting from the text - L2 and vice versus, creation of the map in L2 from the text in L1

Collaborative construction of a Bilingual CMap starting from a single text available in the two languages (the partners will alternate themselves completing the translation in language 1 of parts in language 2 and adding new propositions in language 1, or vice versus)

..................

Along with the Bilingual Concept Maps, where the relations are completely explicit, there are also the BiK-Maps (Bilingual Knowledge Maps) [4], where the link phrases are replaced by a few (nine) link – labels. The BiK-Maps can be created by any student and transformed into “normal” concept maps with explicit relations in L1 and/or in L2, getting helo by the context and the codes. Fig. 8 shows an example of the BiK-map.

Fig. 8 is an example of the BiK-Map derived from a Bilingual-CMap about insects. The abbreviations for the link labels types must be shared in the maps languages.

To read the BiK-Maps, and to transform them into concept maps, it is necessary to decode and infer the relations shortened in link labels suitable to the context and to the related concepts. This is a feasible task for adults and senior students, not for children.

[1] Bahr, S. Danserau, D. Bilingual Knowledge maps (Bi-K Maps) in second language vocabulary learning. Journal of Experimental Education, 70(1), pp. 5-24, 2001.

[2] Wallace, J. And Mintzes, J. J.The Concept Map as a Research Tool: exploring conceptual change in Biology. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 27(10), pp.1033-1052,1990.

[3] R. Richardson, Using Concept Maps as a Cross-Language, su http://www.dlib.vt.edu/~ryanr/Presentations/prelim_Mar_05.ppt

[4] G. Susanne Bahr, Donald F. Dansereau, Bilingual Knowledge (BiK-) MAPS: Study Strategy Effects, http://cmc.ihmc.us/papers/cmc2004-100.pdf